I will be straightforward here: I do not nor have I ever understood the appeal of H.P. Lovecraft. I simply don’t get it. I read him a little in high school (for fun) because I wanted to read a great horror writer and I couldn’t break past the prose. Since then, when I have turned to Lovecraft, once again I find the prose choppy and difficult, but not on purpose. I really love the references to him in the Fallout franchise. The Dunwitch Building at one in the morning is an experience I doubt I ever forget. Usually that is how it typically goes for me: I enjoy references to Lovecraft far more than reading the writer himself.

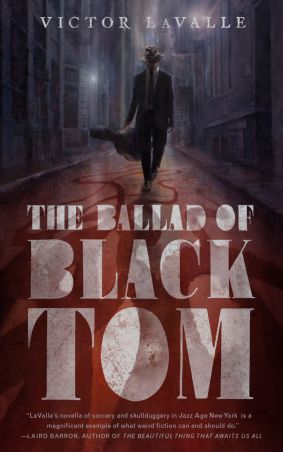

And so this is really what I get for more or less blindly ordering a book that Marlon James posted as a recommendation. The Ballad of Black Tom is a retelling of Lovecraft’s “The Horror at Red Hook.” A Lovecraft story that… I have never read nor tried. I didn’t even realize this until I was more or less done with book and I realized why the name Red Hook sounded so familiar and why the book was dedicated to Lovecraft (I was guessing, based on the cover, that Cthulhu was involved). Some might say that there is no way I could possibly “get” this book without having read Lovecraft first. I think they are right. So here is what I took away from the novella as someone who stupidly did not realize that it was a retelling of Lovecraft’s story.

This is a novella that is brilliant in its use of racial undertones. You could choose to ignore them or you could read too much into them. I perhaps am in the latter camp, but one cannot be so sure. “The Horror at Red Hook” is considered what is perhaps Lovecraft’s most overtly racist story, thus, for a black author (Victor Lavalle) to take on a retelling of it is courageous and thoroughly interesting. What I believe Lavalle does is turn the story into what is simultaneously a reflection, a warning, and a diagnosis. He does this through the character of Thomas Tester. Tester is a young black man from Harlem in the 1920s who lives with his father, his mother having passed in recent years. He partially follows in his father’s footsteps, but he desires to do more in his life than his father did. He won’t work a job that will be taken from him despite any loyalty he has to it. What he must do is make money, and lots of it. This money is what he sees as what will unlock his ability to move beyond Harlem, beyond his struggles. Anyone who has listened to some of the great rap albums from the 90s should see similar themes.

Yet, after being harassed by the police for talking to a white man, he is instructed by his father to take a straight razor with him everywhere. He must hide it at all times, but he needs it for his own protection. This same white man, Mr. Suydam, invites Thomas to play music for him at a party. When Thomas arrives, Suydam instead shows him the power of dark magic and the Outside, a realm that exists beyond space and time. Upon returning home he discovers that his father has been unjustly murdered by the same policemen who harassed him the previous day. Thomas asks how many times his father was shot and the detective tells him that he emptied his clip, reloaded it, and emptied it again. They had mistaken his father’s guitar for a rifle. He returns to the home of Mr. Suydam and as Suydam shows him the lair of “the sleeping king” Thomas leaves the room, despite the cries to Suydam for him to stop.The narrative shifts to the detective who had shot his father. He hears wind of a strange character working under Mr. Suydam going by the name of Black Tom and investigates. That is where I must stop to avoid massive spoilers.

Black Tom is the new moniker for Thomas Tester, he has forgone his previous life after the death of his father. He is working for what is definitely evil, yet this is where Lavalle shines as a brilliant writer. In a confrontation between the detective and Black Tom, one cannot fail to miss the social commentary:

“I bear a hell within me,” Black Tom growled. “And finding myself unsympathized with, wished to tear up the trees, spread havoc and destruction around me, and then to have sat down and enjoyed the ruin.”

“You’re a monster, then,” Malone said.

“I was made one.”

The Ballad of Black Tom, Victor Lavalle

This is the brilliant turn of the book. Whereas the original racism of Lovecraft would most likely be tied in with xenophobia, Lavalle turns this back at Lovecraft. This is an indictment against those that would deny that Black Lives Matter. If you give a person no opportunity, no gateway to success, how can you sit back and self-righteously indict them for exactly what would be expected? What if Lavalle is also warning us, much like at the end of Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp a Butterfly, of what is coming? In Lovecraft it is Cthulhu. Yet what is it in reality? What Lavalle I think brings to mind is the fact that Cthulhu may exist, but nonetheless Cthulhu is always summoned. The symbolism is strong in The Ballad of Black Tom, and I wish greatly that I could go further in depth, but I simply can’t without spoiling it. It must be enough to say that the climax, the meeting between Detective Malone and Black Tom, is otherworldly good.

The Ballad of Black Tom, even to a reader who doesn’t read Lovecraft, appears to accomplish what it sets out to do. Lavalle stays within the lane of what he wants to accomplish, and the novel rewards his readers because it of it.

Recommended to: Those who are fans of H.P. Lovecraft, those who hate H.P. Lovecraft but find him interesting, and those who want to read a book that does a great job of addressing racial issues naturally and cleverly.

Avoid as if it’s me and you’re free money: This book excels at what it does. I highly recommend it to everyone even remotely interested.